BigHornRam

Well-known member

Wolverines: Mystery wrapped in muscle

By MICHAEL JAMISON of the Missoulian

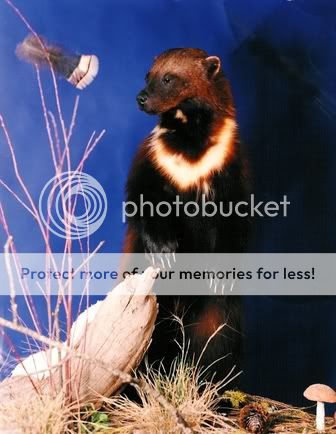

A Glacier Park wolverine.

Photo by Jeff Copeland.

“The wolverine is a tremendous character ... a personality of unmeasured force, courage and achievement, but so enveloped in mists of legend, superstition, idolatry, fear and hatred that one scarcely knows how to begin or what to accept as fact.”

- Ernest Thompson Seton, “Lives of Game Animals”

MANY GLACIER - The slow and steady ring of steel on steel cracked winter's silence, hammer rising and falling with measured cadence as Rick Yates drove the great spike straight through a frozen beaver.

“Beaver's best,” he said between blows. “Lot's of fat and stink. They come with the tails on, usually.”

Yates is the lead field biologist on a project to study wolverines, and the beaver is his bait. He skied into this remote corner of Glacier National Park with carcass in tow, rattling along behind in a makeshift plastic sled.

He crossed through dark subalpine forest, over plank bridges, down snowy slopes and across the frozen expanse of Swiftcurrent Lake to this protected place in the trees, where he kneels, hammer in hand, over the beaver.

Nearby sits a tiny log cabin, about 6-by-3 and 4 feet tall. No windows, no doors; just a 200-pound log lid strapped to a contraption of levers and cables.

It is a wolverine trap.

Wire, threaded through the hole Yates is pounding into his bait, fastens the beaver inside, at the back of the trap. When the wolverine climbs in and tugs on the meat, the wire releases a pair of vice grips, which releases a cable, which releases the lid, which drops into place with a startling bang.

He uses log traps because an ensnared wolverine, in its dogged ferocity, would snap its teeth trying to chew out of a metal trap. But the problem with this cabin is, if you don't let him out soon enough, a wolverine will just eat his way out through 8-inch logs and amble off about his business.

“They're all teeth and muscle,” Yates marvels.

Even the lid, which outweighs the wolverine by a full order of magnitude, must lock when it falls, because “if they can get any purchase at all, they'll push the lid up. These animals are just tremendously powerful.”

They are also tremendously few and far between, “probably the lowest-density carnivore in North America, maybe the world,” said project leader Jeff Copeland. “It always amazes me that they can persist at these densities.”

Cover 500 square miles of suitable habitat, he said, and you might find a half-dozen wolverines.

So how a boy Gulo gulo luscus finds a girl Gulo gulo luscus in all that wilderness, and how well the pair succeeds in producing a litter of kits, is of considerable interest to scientists like Copeland - scientists who admit, in his words, they “really don't know much.”

One thing he does know, however, is that the animal's historic range is shrinking. The California wolverine is gone, as is Colorado's. A few remain in the Sawtooths and down in Wyoming, but when it comes to dependable populations of wolverines in the Lower 48, Copeland said, “Montana is pretty much it.”

And in Montana, the Many Glacier Valley is pretty much it. Here, five big valleys spill into a hub of habitat crossings, and here Yates has staked his beaver.

Jeff Copeland was reading an article on heli-skiing when the notion struck that backcountry skiers and snowmobilers prefer the same sorts of habitat, and it just happens to be wolverine habitat.

Specifically, it happens to be the sort of steep mountain place female wolverines like to den in with a litter of kits.

He'd been reading up on wolverines, about how hunters in Norway and Sweden would raise a ruckus at the den site to force mom to grab the kits and run.

“We knew from those reports that disturbance would push them out of the den,” Copeland said, “and as I read about the heli-skiing, I began to wonder if this is a problem.”

At the time, Copeland was working for Idaho Fish and Game, and he knew land managers had long been pushing winter recreationists higher and higher to get them out of lowland winter ranges.

“But what,” he suddenly wondered, “is that doing to the wolverines?”

And so when Rick Yates surprised everyone a few years back by winning a three-year $180,000 National Park Service grant to study the elusive weasels, Copeland jumped at the chance.

He'd been tracking the critters in Idaho and elsewhere, and was now working at the U.S. Forest Service's Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula. Yates' funding, he knew, was a perfect opportunity to continue his studies of wolverine dens.

Where are they, generally, and why are they where they are?

Copeland's been at it four years now, and is just starting to understand a few things. It looks like wolverines aren't quite the loners everyone thought, looks like females are setting the social calendar and like kit survival is pretty slim.

And it looks like wolverines like goats almost as much as frozen beaver.

Copeland revs the government Suburban, picks up a head of steam and hits the 5-foot snowdrift hard, bouncing airborne before sliding out the other side.

“That was harder than it looked,” he says, slightly wild-eyed.

This is the road into Many Glacier, snowed shut and locked tight for the winter. But Copeland has a key, and as he swings the gate open he declares that “from here on in, Glacier National Park is all ours.”

Well, not quite.

Just below the road a coyote runs hard, tail flat out behind, snatching glimpses every so often into the sky over his left shoulder. There, three golden eagles fly in hot pursuit, breaking away only when the coyote finally gains the timber at river's edge.

Above, on wildly windswept hillsides, bighorn sheep pick through a slim winter diet. Lynx cross tracks with moose in willow bottoms, and even show up in Yates' wolverine traps now and again.

Above it all, mountains shine in clear evening air and the day's last rays filter through in tremendous columns, the light and height turning Grinnell Point into a wild-crafted cathedral.

The road sign says “Keep Right,” but Copeland steers left, where the drift is smaller. There's no one to care, and the farther you go the closer the mountains feel, horizon foreshortened as sky gives way to rock and ice and snow drifted to cabin's crest.

Yates is waiting at road's end, in a backcountry cabin with front-country amenities, the winter base camp from which he follows the wolverines. It's the sort of place where you melt snow on the wood stove for water - the sort of place where people keep lynx scat in carefully labeled paper bags, looking for all the world like hairy little Baby Ruth candy bars.

At one time, Yates and a crew kept 10 traps - a couple up Belly River, a couple at Two Medicine, one each up Cut Bank and Avalanche creeks - all baited with beaver carcasses bought from fur trappers at a quick $5 apiece. But now, only the four traps here at Many Glacier are rigged.

“We're on short rations,” Yates explains, with the three-year study now entering year four and funding scarcer than wolverines.

He stays in the backcountry almost all winter, until the grizzlies wake up in March or April.

“When we see the first bear, we're done,” he said.

After all, it's tough duty dragging dead beavers around the park with grizzlies on patrol, “and the bears just tear the hell out of the traps, anyway, throwing the lids around and destroying everything.”

Amazing, then, that a wolverine can hold its own against a grizzly, that a 30-pound animal the size of a 5-year-old can cover all these wilderness miles, up and down mountains and back up again.

“They are amazingly ferocious beasts,” Copeland said.

“I've seen a grizzly bear go out of its way to avoid a wolverine,” Yates added.

“Yet we hardly even know them,” Copeland concludes. “They're still a mystery.”

Under the harsh glare of a flashlight beam the wolverine paced, lashed out, recoiled, lashed again. A trapped wolverine is wholly unlike any other animal, except perhaps that famous Tasmanian Devil from Saturday mornings.

Hissing, spitting, growling, snarling, slathering, gnashing, rumbling - it's not a place to stick your hand. “I've had them take flashlights from people and just eat the whole thing, batteries and all,” Copeland said.

When they fight, they fight from their backs, turning tooth and claw into their opponent's underbelly.

“Oh, they can put up a fuss,” Copeland said. And what, exactly, does a wolverine fuss look like? “A fuss looks like teeth, is what it looks like - teeth and claws.”

You're left, finally, with a distinct sense of relief that wolverines so seldom cross our paths, that they remain, as Copeland says, “a mystery.”

Twice, the federal government has been petitioned to place wolverines under the protection of the Endangered Species Act. Twice, the feds have declined, saying there simply is not enough known about the animals to justify a listing.

But the mystery called wolverine has become Copeland's lifework, a riddle to which he is slowly teasing out answers.

He's plumbed ancient DNA culled from museum collections, pored over trapping records, followed a trail of superstition far into the bright white heart of winter. Along the way, he's turned chemist to get a whiff of what that wolverine nose is picking up, turned trapper to catch and collar 19 different animals here in Glacier Park.

Finally, the trickle of data is paying off. He's plotted wolverines in a particular habitat of extended snow, hinting that they prefer places where winter's weight still presses hard well into spring. He's dug into their snowy dens, catching kits, even finding the leftover bones from winter feasts: birds and beasts and small luckless rodents.

And he's followed them straight over mountaintops, up high where he thinks they're preying on mountain goats. (“It's still a hypothesis, but every time Rick would go into a den, he'd come back with goat pieces. And what else are they doing up there?”)

Turns out, wolverines climb these cliffs as if they have a good dose of goat in them, as well, and with Global Positioning System data pegging their location every five minutes the veil of mystery is quickly parting.

As it does, the myth of the solitary scavenger comes apart at the seams, replaced by a more complex and wonderful narrative, the center of which is mom.

“I think that the social structure of the wolverine is totally female controlled,” Copeland said.

That is to say, the females choose their smaller home ranges with considerable care, picking places with good food, shelter and den sites. The males basically follow along, their larger home ranges dictated by the choices of their many mates.

Females, Copeland said, seem to be faithful to a single male, who in turn has three or four families. While mom and kits are in the den, he said, the male is traveling a circuit, from den to den to den, checking on mates and kits, marking his way with scent, eating on the run.

He might make 10 miles an hour on average, sleeping a few hours, running a few hours, on and off around the clock, tracking hundreds of wilderness miles on stubby 6-inch legs.

Often, Copeland said, we tend to think of male animals keeping a close-knit harem of females and fighting off all challengers. But that hardly makes sense with a critter whose three or four mates are spread out across 500 square miles.

“He simply couldn't control it,” the researcher said.

And so Copeland's beginning to think the wolverine relies on his female's fidelity, to the fact that she's only receptive to him, and he uses his energy to travel constantly, from den to den, rather than fighting for the chance to mate.

Over time, he said, the genetics in an area tend to clump, with all the youngsters coming from one father.

And to everyone's surprise, he's an attentive father, crawling into the den to sleep with his kits, playing, wrestling, allowing the youngsters to travel with him for a while each spring.

“We're starting to think they're actually very social,” Copeland said.

How well these hypotheses will hold up, however, remains to be seen.

“If we can keep going another five years,” he said, “we might be able to talk about these things with much more certainty.”

With more time, he hopes to ferret out “how the animal moves across the landscape and the rate at which it moves.”

Does it linger in certain habitat types? Avoid certain kinds of places? Return to spots again and again? Hang out near den sites? Near food sources?

Answers to those questions could help pinpoint conservation efforts across the country's ever-shrinking wolverine range, and could change winter recreation for the rest of us.

If wolverines den in a specific type of place, then conservation of those places should be pretty straightforward. But if they're generalists, then perhaps winter recreation isn't such a big deal.

So far, Copeland has identified and monitored three dens in Glacier Park; it might not seem like much, but it represents 50 percent of all the wolverine dens ever found in the Lower 48.

“There's so much work left out there,” he said. “We really don't know as much as we think we do, and we don't know near as much as we should.”

And with that great unknown, Copeland's driven back into the winter, skiing beneath soaring peaks with telemetry antennae in hand. Yates is right behind, dragging yet another beaver, tracking an animal he hardly knows, a beast he calls “the wilderness itself.”

By MICHAEL JAMISON of the Missoulian

A Glacier Park wolverine.

Photo by Jeff Copeland.

“The wolverine is a tremendous character ... a personality of unmeasured force, courage and achievement, but so enveloped in mists of legend, superstition, idolatry, fear and hatred that one scarcely knows how to begin or what to accept as fact.”

- Ernest Thompson Seton, “Lives of Game Animals”

MANY GLACIER - The slow and steady ring of steel on steel cracked winter's silence, hammer rising and falling with measured cadence as Rick Yates drove the great spike straight through a frozen beaver.

“Beaver's best,” he said between blows. “Lot's of fat and stink. They come with the tails on, usually.”

Yates is the lead field biologist on a project to study wolverines, and the beaver is his bait. He skied into this remote corner of Glacier National Park with carcass in tow, rattling along behind in a makeshift plastic sled.

He crossed through dark subalpine forest, over plank bridges, down snowy slopes and across the frozen expanse of Swiftcurrent Lake to this protected place in the trees, where he kneels, hammer in hand, over the beaver.

Nearby sits a tiny log cabin, about 6-by-3 and 4 feet tall. No windows, no doors; just a 200-pound log lid strapped to a contraption of levers and cables.

It is a wolverine trap.

Wire, threaded through the hole Yates is pounding into his bait, fastens the beaver inside, at the back of the trap. When the wolverine climbs in and tugs on the meat, the wire releases a pair of vice grips, which releases a cable, which releases the lid, which drops into place with a startling bang.

He uses log traps because an ensnared wolverine, in its dogged ferocity, would snap its teeth trying to chew out of a metal trap. But the problem with this cabin is, if you don't let him out soon enough, a wolverine will just eat his way out through 8-inch logs and amble off about his business.

“They're all teeth and muscle,” Yates marvels.

Even the lid, which outweighs the wolverine by a full order of magnitude, must lock when it falls, because “if they can get any purchase at all, they'll push the lid up. These animals are just tremendously powerful.”

They are also tremendously few and far between, “probably the lowest-density carnivore in North America, maybe the world,” said project leader Jeff Copeland. “It always amazes me that they can persist at these densities.”

Cover 500 square miles of suitable habitat, he said, and you might find a half-dozen wolverines.

So how a boy Gulo gulo luscus finds a girl Gulo gulo luscus in all that wilderness, and how well the pair succeeds in producing a litter of kits, is of considerable interest to scientists like Copeland - scientists who admit, in his words, they “really don't know much.”

One thing he does know, however, is that the animal's historic range is shrinking. The California wolverine is gone, as is Colorado's. A few remain in the Sawtooths and down in Wyoming, but when it comes to dependable populations of wolverines in the Lower 48, Copeland said, “Montana is pretty much it.”

And in Montana, the Many Glacier Valley is pretty much it. Here, five big valleys spill into a hub of habitat crossings, and here Yates has staked his beaver.

Jeff Copeland was reading an article on heli-skiing when the notion struck that backcountry skiers and snowmobilers prefer the same sorts of habitat, and it just happens to be wolverine habitat.

Specifically, it happens to be the sort of steep mountain place female wolverines like to den in with a litter of kits.

He'd been reading up on wolverines, about how hunters in Norway and Sweden would raise a ruckus at the den site to force mom to grab the kits and run.

“We knew from those reports that disturbance would push them out of the den,” Copeland said, “and as I read about the heli-skiing, I began to wonder if this is a problem.”

At the time, Copeland was working for Idaho Fish and Game, and he knew land managers had long been pushing winter recreationists higher and higher to get them out of lowland winter ranges.

“But what,” he suddenly wondered, “is that doing to the wolverines?”

And so when Rick Yates surprised everyone a few years back by winning a three-year $180,000 National Park Service grant to study the elusive weasels, Copeland jumped at the chance.

He'd been tracking the critters in Idaho and elsewhere, and was now working at the U.S. Forest Service's Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula. Yates' funding, he knew, was a perfect opportunity to continue his studies of wolverine dens.

Where are they, generally, and why are they where they are?

Copeland's been at it four years now, and is just starting to understand a few things. It looks like wolverines aren't quite the loners everyone thought, looks like females are setting the social calendar and like kit survival is pretty slim.

And it looks like wolverines like goats almost as much as frozen beaver.

Copeland revs the government Suburban, picks up a head of steam and hits the 5-foot snowdrift hard, bouncing airborne before sliding out the other side.

“That was harder than it looked,” he says, slightly wild-eyed.

This is the road into Many Glacier, snowed shut and locked tight for the winter. But Copeland has a key, and as he swings the gate open he declares that “from here on in, Glacier National Park is all ours.”

Well, not quite.

Just below the road a coyote runs hard, tail flat out behind, snatching glimpses every so often into the sky over his left shoulder. There, three golden eagles fly in hot pursuit, breaking away only when the coyote finally gains the timber at river's edge.

Above, on wildly windswept hillsides, bighorn sheep pick through a slim winter diet. Lynx cross tracks with moose in willow bottoms, and even show up in Yates' wolverine traps now and again.

Above it all, mountains shine in clear evening air and the day's last rays filter through in tremendous columns, the light and height turning Grinnell Point into a wild-crafted cathedral.

The road sign says “Keep Right,” but Copeland steers left, where the drift is smaller. There's no one to care, and the farther you go the closer the mountains feel, horizon foreshortened as sky gives way to rock and ice and snow drifted to cabin's crest.

Yates is waiting at road's end, in a backcountry cabin with front-country amenities, the winter base camp from which he follows the wolverines. It's the sort of place where you melt snow on the wood stove for water - the sort of place where people keep lynx scat in carefully labeled paper bags, looking for all the world like hairy little Baby Ruth candy bars.

At one time, Yates and a crew kept 10 traps - a couple up Belly River, a couple at Two Medicine, one each up Cut Bank and Avalanche creeks - all baited with beaver carcasses bought from fur trappers at a quick $5 apiece. But now, only the four traps here at Many Glacier are rigged.

“We're on short rations,” Yates explains, with the three-year study now entering year four and funding scarcer than wolverines.

He stays in the backcountry almost all winter, until the grizzlies wake up in March or April.

“When we see the first bear, we're done,” he said.

After all, it's tough duty dragging dead beavers around the park with grizzlies on patrol, “and the bears just tear the hell out of the traps, anyway, throwing the lids around and destroying everything.”

Amazing, then, that a wolverine can hold its own against a grizzly, that a 30-pound animal the size of a 5-year-old can cover all these wilderness miles, up and down mountains and back up again.

“They are amazingly ferocious beasts,” Copeland said.

“I've seen a grizzly bear go out of its way to avoid a wolverine,” Yates added.

“Yet we hardly even know them,” Copeland concludes. “They're still a mystery.”

Under the harsh glare of a flashlight beam the wolverine paced, lashed out, recoiled, lashed again. A trapped wolverine is wholly unlike any other animal, except perhaps that famous Tasmanian Devil from Saturday mornings.

Hissing, spitting, growling, snarling, slathering, gnashing, rumbling - it's not a place to stick your hand. “I've had them take flashlights from people and just eat the whole thing, batteries and all,” Copeland said.

When they fight, they fight from their backs, turning tooth and claw into their opponent's underbelly.

“Oh, they can put up a fuss,” Copeland said. And what, exactly, does a wolverine fuss look like? “A fuss looks like teeth, is what it looks like - teeth and claws.”

You're left, finally, with a distinct sense of relief that wolverines so seldom cross our paths, that they remain, as Copeland says, “a mystery.”

Twice, the federal government has been petitioned to place wolverines under the protection of the Endangered Species Act. Twice, the feds have declined, saying there simply is not enough known about the animals to justify a listing.

But the mystery called wolverine has become Copeland's lifework, a riddle to which he is slowly teasing out answers.

He's plumbed ancient DNA culled from museum collections, pored over trapping records, followed a trail of superstition far into the bright white heart of winter. Along the way, he's turned chemist to get a whiff of what that wolverine nose is picking up, turned trapper to catch and collar 19 different animals here in Glacier Park.

Finally, the trickle of data is paying off. He's plotted wolverines in a particular habitat of extended snow, hinting that they prefer places where winter's weight still presses hard well into spring. He's dug into their snowy dens, catching kits, even finding the leftover bones from winter feasts: birds and beasts and small luckless rodents.

And he's followed them straight over mountaintops, up high where he thinks they're preying on mountain goats. (“It's still a hypothesis, but every time Rick would go into a den, he'd come back with goat pieces. And what else are they doing up there?”)

Turns out, wolverines climb these cliffs as if they have a good dose of goat in them, as well, and with Global Positioning System data pegging their location every five minutes the veil of mystery is quickly parting.

As it does, the myth of the solitary scavenger comes apart at the seams, replaced by a more complex and wonderful narrative, the center of which is mom.

“I think that the social structure of the wolverine is totally female controlled,” Copeland said.

That is to say, the females choose their smaller home ranges with considerable care, picking places with good food, shelter and den sites. The males basically follow along, their larger home ranges dictated by the choices of their many mates.

Females, Copeland said, seem to be faithful to a single male, who in turn has three or four families. While mom and kits are in the den, he said, the male is traveling a circuit, from den to den to den, checking on mates and kits, marking his way with scent, eating on the run.

He might make 10 miles an hour on average, sleeping a few hours, running a few hours, on and off around the clock, tracking hundreds of wilderness miles on stubby 6-inch legs.

Often, Copeland said, we tend to think of male animals keeping a close-knit harem of females and fighting off all challengers. But that hardly makes sense with a critter whose three or four mates are spread out across 500 square miles.

“He simply couldn't control it,” the researcher said.

And so Copeland's beginning to think the wolverine relies on his female's fidelity, to the fact that she's only receptive to him, and he uses his energy to travel constantly, from den to den, rather than fighting for the chance to mate.

Over time, he said, the genetics in an area tend to clump, with all the youngsters coming from one father.

And to everyone's surprise, he's an attentive father, crawling into the den to sleep with his kits, playing, wrestling, allowing the youngsters to travel with him for a while each spring.

“We're starting to think they're actually very social,” Copeland said.

How well these hypotheses will hold up, however, remains to be seen.

“If we can keep going another five years,” he said, “we might be able to talk about these things with much more certainty.”

With more time, he hopes to ferret out “how the animal moves across the landscape and the rate at which it moves.”

Does it linger in certain habitat types? Avoid certain kinds of places? Return to spots again and again? Hang out near den sites? Near food sources?

Answers to those questions could help pinpoint conservation efforts across the country's ever-shrinking wolverine range, and could change winter recreation for the rest of us.

If wolverines den in a specific type of place, then conservation of those places should be pretty straightforward. But if they're generalists, then perhaps winter recreation isn't such a big deal.

So far, Copeland has identified and monitored three dens in Glacier Park; it might not seem like much, but it represents 50 percent of all the wolverine dens ever found in the Lower 48.

“There's so much work left out there,” he said. “We really don't know as much as we think we do, and we don't know near as much as we should.”

And with that great unknown, Copeland's driven back into the winter, skiing beneath soaring peaks with telemetry antennae in hand. Yates is right behind, dragging yet another beaver, tracking an animal he hardly knows, a beast he calls “the wilderness itself.”