Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Fire Science and Wild Sheep

- Thread starter BigHornRam

- Start date

jdf

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 1, 2011

- Messages

- 518

Thanks for article.

I see turkeys all the time walk right back in our burn units while still smoking the same day as we burn them.

I see turkeys all the time walk right back in our burn units while still smoking the same day as we burn them.

Salmonchaser

Well-known member

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2019

- Messages

- 2,941

Love it when I get to read something that supports my understanding as a lay person. Spent two weeks hunting this year near Thompson falls. There have been some dramatic fires in there but the most interesting areas are where recent fires overlapped ten or twenty year old burns. That is where we really saw critters, including sheep.

That's a great article on selective and precise use and benefits of small scale, low intensity burns. Well planned burns can benefit critical wildlife habitat.

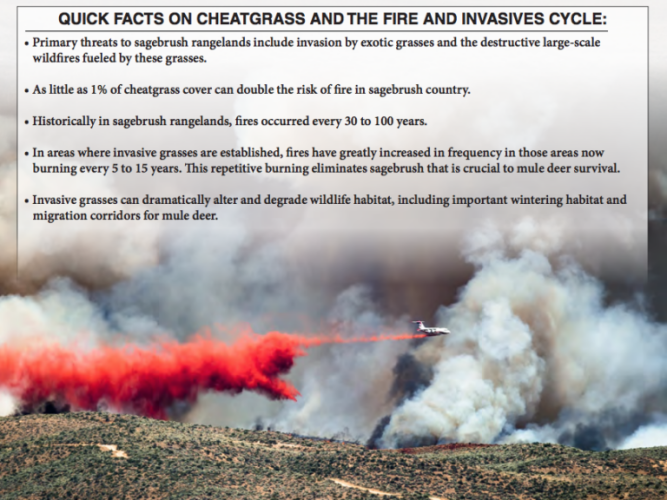

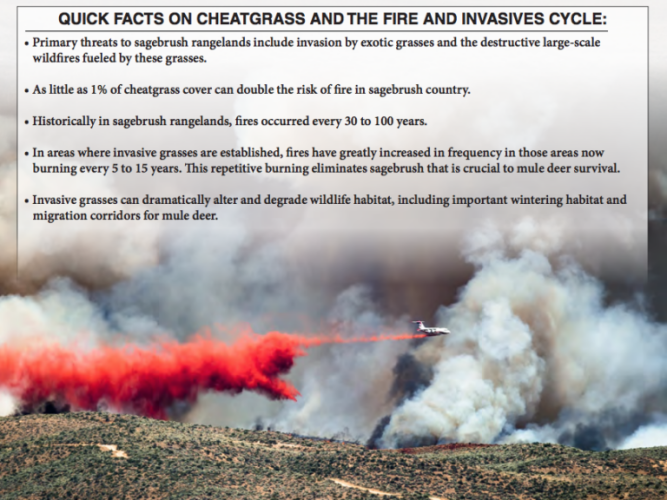

As mentioned several times in the article, not all fire is good. A prime example of this is high intensity and large-scale devastation of native browse fueled by dense, cheatgrass fed wildfires. Historically wildfires occurred every 30 to 100 years, however, cheatgrass infested areas across the West have increased the wildfire frequency to now burning 5 to 15 years. Larger-scale, higher intensity fires have thinned and even eliminated sagebrush, mountain mahogany, antelope bitterbrush and other browse species that are critical cover and food for mule deer and other game animals' survival.

iwjv.org

iwjv.org

Here are a few inserts from the thin horned sheep article:

'Across the West, one thing is clear: when it’s done right, fire brings habitat back to life. For bighorns, prescribed burning opens slopes and renews the grasses they depend on through long winters. For thinhorns, the same is true, but fire must be used carefully, since the alpine range recovers more slowly, and too much heat can do lasting damage.

That balance of knowing where and when to use fire is central to WSF’s conservation work. From Idaho to Wyoming to northern British Columbia, the focus is on combining field experience with solid science to manage habitat that keeps wild sheep healthy and on the mountain.

“For thinhorns, your Stone’s and Dall’s sheep, you’re looking at natural fire return intervals of roughly one hundred fifty to three hundred years,” Jex said. “Fire just doesn’t play the same role there. The plant communities recover more slowly, and many species of thinhorn rely on them and don’t come back quickly. They feed on more than a hundred different plants. After a massive burn, you might get a quarter of those back. So, in some areas, fire can do more harm than good.”

Large wildfires in recent years have also changed the equation.

“When you get these broad-scale fires, you create a flush of forage that draws in elk and bison,” Jex said. “And where those go, wolves, bears, and cougars follow. You end up with more predators in sheep country.”

Yet Jex stresses that fire, when handled carefully, remains one of the most valuable tools available. “Prescribed fire has a place, even in thinhorn country,” he said. “If you do it on a small scale and in the right locations, like lambing areas or key winter ranges, you can really improve visibility and forage for Stone’s sheep.”

As mentioned several times in the article, not all fire is good. A prime example of this is high intensity and large-scale devastation of native browse fueled by dense, cheatgrass fed wildfires. Historically wildfires occurred every 30 to 100 years, however, cheatgrass infested areas across the West have increased the wildfire frequency to now burning 5 to 15 years. Larger-scale, higher intensity fires have thinned and even eliminated sagebrush, mountain mahogany, antelope bitterbrush and other browse species that are critical cover and food for mule deer and other game animals' survival.

Cheating Mule Deer in the Sage - IWJV

“There are excellent wildlife managers out there and we can do our part in supporting their efforts by advocating for sufficient funding and policy measures to keep conservation happening. The Mule Deer Foundation is proud to partner with them across the West."

Here are a few inserts from the thin horned sheep article:

'Across the West, one thing is clear: when it’s done right, fire brings habitat back to life. For bighorns, prescribed burning opens slopes and renews the grasses they depend on through long winters. For thinhorns, the same is true, but fire must be used carefully, since the alpine range recovers more slowly, and too much heat can do lasting damage.

That balance of knowing where and when to use fire is central to WSF’s conservation work. From Idaho to Wyoming to northern British Columbia, the focus is on combining field experience with solid science to manage habitat that keeps wild sheep healthy and on the mountain.

“For thinhorns, your Stone’s and Dall’s sheep, you’re looking at natural fire return intervals of roughly one hundred fifty to three hundred years,” Jex said. “Fire just doesn’t play the same role there. The plant communities recover more slowly, and many species of thinhorn rely on them and don’t come back quickly. They feed on more than a hundred different plants. After a massive burn, you might get a quarter of those back. So, in some areas, fire can do more harm than good.”

Large wildfires in recent years have also changed the equation.

“When you get these broad-scale fires, you create a flush of forage that draws in elk and bison,” Jex said. “And where those go, wolves, bears, and cougars follow. You end up with more predators in sheep country.”

Yet Jex stresses that fire, when handled carefully, remains one of the most valuable tools available. “Prescribed fire has a place, even in thinhorn country,” he said. “If you do it on a small scale and in the right locations, like lambing areas or key winter ranges, you can really improve visibility and forage for Stone’s sheep.”

Last edited:

Gerald Martin

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 3, 2009

- Messages

- 9,479

BigHornRam

Well-known member

Seems like that place burns every other year, and it has a heavy crop of cheat grass. Sheep sure do like it, and do well there.Timely article. The unit I had my tag in a few years ago burned this summer. I was passing through the area on my way to Thanksgiving and a significant portion of the unit’s sheep population was on the new grass in the burn.

One was a cranker of a ram. It would have been a good year for the tag…View attachment 394421View attachment 394422

Sheep may eat cheatgrass when it's green but the thing about cheatgrass is that the nutrition value is extremely low even when it's green. By June, cheatgrass is dried up, dead, and has 0 nutrition value. It displaces a lot of other native species that are higher in nutrition through the entire growing season. If there have been several wildfires in that area that have been fueled by cheatgrass there likely are very few desirable native species remaining. The sheep may eat cheatgrass because they have no other option and there is nothing else available this time of year? Overall, I bet the sheep would be in a lot better shape if there were natives rather than cheatgrass in that site.

I see the total opposite in the spring in our winter ranges here in Colorado where we've controlled cheatgrass. The deer, elk, sheep, and other big game species are concentrated in areas where cheatgrass has been controlled. Spring is a critical time of year and they are keying in on high quality, nutritious natives that are greening up and have dramatically increased where there previously was dense cheatgrass.

I see the total opposite in the spring in our winter ranges here in Colorado where we've controlled cheatgrass. The deer, elk, sheep, and other big game species are concentrated in areas where cheatgrass has been controlled. Spring is a critical time of year and they are keying in on high quality, nutritious natives that are greening up and have dramatically increased where there previously was dense cheatgrass.

Last edited:

Here is an interesting article about mule deer and cheatgrass.

wyofile.com

wyofile.com

Mule deer could lose half their northeast Wyoming habitat to cheatgrass without help - WyoFile

New study shows deer avoid cheatgrass-covered areas, but authors also provide hope.

Flynarrow

Well-known member

As comments here suggest, there is a variety of landscapes that respond differently to fire. Some elevations containing sage with cheat grass can respond with only cheatgrass, eliminating sage for long periods or longer. Here in western Montana we have far more mature forest acres now than in the past due to fire suppression. While some can/has been set back in seral vegetation due to logging, much of many landscapes are infeasible to log but fire suppression continues. Prescribed fire is an option on a limited number of acres due to forest over story, elevation, etc plus limited resources and limited time frames. We need to recognize that many wildfires benefit a host of species, including most ungulates. Repeat burns in burned over acres reduces the heavy downfall that clogs otherwise beneficial conditions, but currently burned areas are used as control boundaries for any subsequent fires in the area. We need to loosen the constraints in allowing wildfire over many more landscapes if we are to encourage big game to utilize public lands over the long term.

I can always tell a cheatgrass-fueled fire because the area is totally black char. Even the lichens in the soil and on rock that take centuries to grow a few inches totally burn!

We've had prescribed burns and wildfires that burn through areas we've controlled cheatgrass. Those fires burn with a fraction of the heat and intensity with a mosaic burn pattern.

We've had prescribed burns and wildfires that burn through areas we've controlled cheatgrass. Those fires burn with a fraction of the heat and intensity with a mosaic burn pattern.

Last edited:

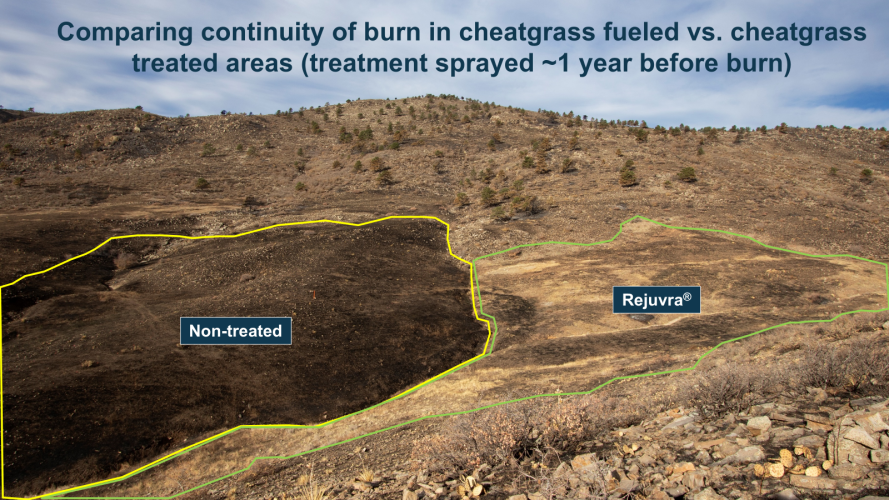

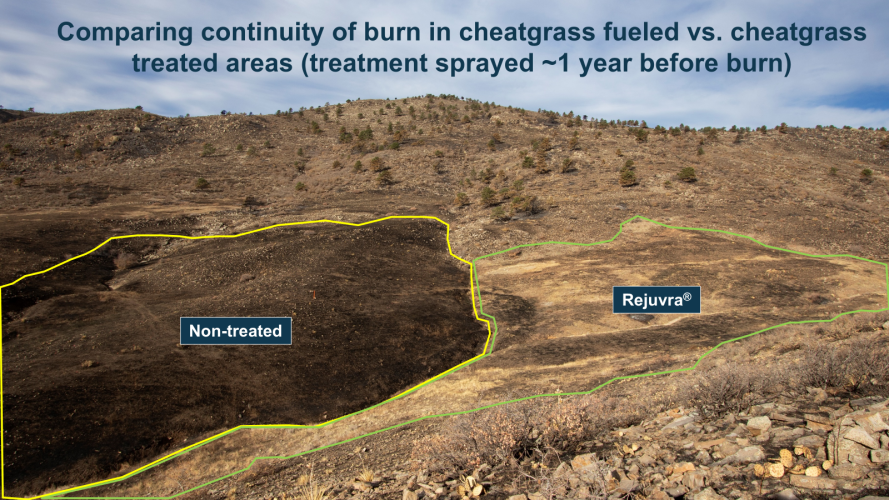

I thought I would include a few photos from properties here in Colorado after the Calwood Wildfire in 2020 that compare burn severity of cheatgrass infested vs cheatgrass controlled sites.

The photo above shows the contrast in native species vs fine-fueled continuous cheatgrass in sprayed (foreground) vs nonsprayed sites (background) prior to a wildfire.

The foreground area in the above photo was sprayed with Rejuvra the year prior to the Calwood Wildfire (mosaic burn). The black area in the background was not sprayed and was a continuous stand of dense cheatgrass (high intensity burn).

This shows a larger birds-eye view of the same nontreated area with dense cheatgrass vs an adjacent sprayed area that was sprayed the year before the Calwood Wildfire.

This is a prime example of what happens when there is dense, continuous stand of dense cheatgrass fine fuels on the ground and understory of shrubs. Notice the line just past the dead shrubs where there is still native grass after the wildfire where cheatgrass had been controlled. There are live shrubs and native grass that hardly burned in the line above the blackened area.

This is an example showing a fire break area that was sprayed the year before the wildfire, with minimal fine-fuel to carry the wildfire.

The photo above shows the contrast in native species vs fine-fueled continuous cheatgrass in sprayed (foreground) vs nonsprayed sites (background) prior to a wildfire.

The foreground area in the above photo was sprayed with Rejuvra the year prior to the Calwood Wildfire (mosaic burn). The black area in the background was not sprayed and was a continuous stand of dense cheatgrass (high intensity burn).

This shows a larger birds-eye view of the same nontreated area with dense cheatgrass vs an adjacent sprayed area that was sprayed the year before the Calwood Wildfire.

This is a prime example of what happens when there is dense, continuous stand of dense cheatgrass fine fuels on the ground and understory of shrubs. Notice the line just past the dead shrubs where there is still native grass after the wildfire where cheatgrass had been controlled. There are live shrubs and native grass that hardly burned in the line above the blackened area.

This is an example showing a fire break area that was sprayed the year before the wildfire, with minimal fine-fuel to carry the wildfire.

Last edited:

KMO385

Active member

I see quail do the same thing, like minutes after the fire goes by. It makes foraging alive easier. I also see elk using burned areas a lot too. They love that new growth, and on those sunny days in the winter the grounds gets little bit warmer for them to lounge on. The best part is other hunters overlook those areas. But I also feel like a duffus walking around for upland birds, it looks wierd.Thanks for article.

I see turkeys all the time walk right back in our burn units while still smoking the same day as we burn them.

KMO385

Active member

I know it is, cheatgrass has altered the fire regime out there. Along with juniper/confir encroachment as well. I think most people agree that fire in sagebrush ecosystems where cheatgrass is present generally leads to a takeover by cheatgrass. The sage steppe is interesting ecosystem in its fire ecology, depending of region, sagebrush species fire regimes vary 50ish years to over 400. Small scale fires (<5 acres) before cheatgrass were beneficial for grouse lekking sites, the establishment of other native forbs and bunch grasses and other wildlife. Im a bit rusty with the lifestyle of cheatgrass, but could or has fire been tried to be introduced in cheatgrass monocultures during growing seasons to decease seed production? Along with the reseeding in early sectional sage steppe grasses and forbs species. Theres a lot material and studies out there to one think different ways to tackle the cheatgrass problem only if funding was unlimited.

Here’s an in-depth BLM article on cheatgrass and wildfire.

kwyeewyk

Well-known member

Not specific to sheep but does touch on sheep, kind of a general and feel-good review, but hits the main points.

KMO385

Active member

Thanks for posting that! Good read. If your into sage steepe fire ecology and the cheatgrass fires problem I'll have to take some time to go through some out resource material, theres some fascinating data out there if you'd like to read it. I think we're gonna have a data gap in the near term future though.Here’s an in-depth BLM article on cheatgrass and wildfire.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 486

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 2K